- Welcome to FictionDB, Guest

- | My Account

- | Help

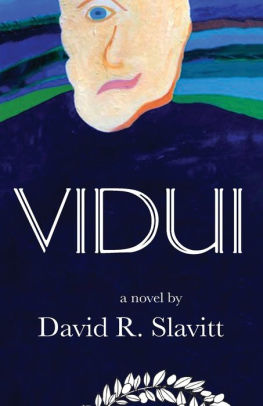

Vidui — David R. Slavitt

2021-10-08Slavitt (Day Sailing, 2018, etc.) chronicles the final days of a dying man in this metafictional novel.The Vidui, the author explains, is Judaism’s final prayer, to be recited in moments of imminent death. It’s “not so much a confession, although that is the usual translation of the Hebrew word, as an acknowledgment,” the narrator notes. The dying person, in this case, is Vernon Dewey (or “V. Dewey”). He lies in bed, surrounded by family, although both the room and the family are vaguely described, at first. At one point, he pretends to be asleep, so that he can hear what his relatives might say about him; he moves his left foot slightly, just to see if anyone will notice. He later considers how he feels about the people who have wronged him over the course of his life. As Vernon lies in the bed, the narrator ruminates on all things relating to death: religions, medicine, the concept of legacy, literature, grief, regret, boredom, humiliation. As loquacious as the narrator is, Vernon is the opposite. In fact, he’s having trouble thinking of things to say to those around him—or even deciding if he wants to say anything at all. (At one point, when his grandson Jacob tells him that it’s okay that they aren’t saying much to each other, Vernon says, relieved, “I was worried that you might ask me something stupid, like ‘Did you like your life?’ ”) But can he think of a worthwhile statement before the end comes? Or maybe even a prayer? The isolation of death, and the inability of language or action or sentiment to remedy that isolation, is the main theme of this novel. As a result, there’s little in the way of a traditional plot. Slavitt—or the godlike narrator, whoever he may be—admits as much several times, even applauding the reader for continuing on despite that fact. Indeed, the narrator is the main presence in the novel, and readers are asked to consider his thoughts on wordplay, Schrödinger’s cat, and famous fictional frogs before being introduced to Vernon. Thereafter, the prose is mostly clever and engaging: “Lately, Vernon has not bothered to read the obituaries, the section of the paper to which (until recently) he turned first, because that was the only real news. He was like one of those noblemen who has a chart on the wall and with each death gets closer to inheriting the throne.” Slavitt does, however, enjoy puns to a degree that may offend a certain portion of his potential readership: “Is there a plot? Actually, yes. Vernon’s parents bought a plot with room for four graves.” The novel is rather short at 125 pages, but even so, readers must work to get to the end, and despite Slavitt’s obvious gifts as a writer and thinker, it isn’t quite as satisfying as conceptual anti-novels by other writers, such as the late David Markson.An extended riff on deathbed scenes that doesn’t transcend its static premise.

Sub-Genres

Click on any of the links above to see more books like this one.

EDITIONS

Sign in to see more editions-

- First Edition

- Nov-2019

- Livingston Press at the University of West Al

- Trade Paperback

- ISBN: 1604892315

- ISBN13: 9781604892314