- Welcome to FictionDB, Guest

- | My Account

- | Help

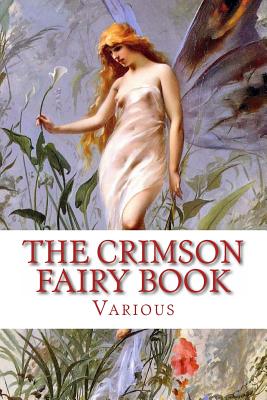

The Crimson Fairy Book — Createspace

Each Fairy Book demands a preface from the Editor, and these introductions are inevitably bothmonotonous and unavailing. A sense of literary honesty compels the Editor to keep repeating thathe is the Editor, and not the author of the Fairy Tales, just as a distinguished man of science is onlythe Editor, not the Author of Nature. Like nature, popular tales are too vast to be the creation of asingle modern mind. The Editor's business is to hunt for collections of these stories told by peasantor savage grandmothers in many climes, from New Caledonia to Zululand; from the frozen snowsof the Polar regions to Greece, or Spain, or Italy, or far Lochaber. When the tales are found they areadapted to the needs of British children by various hands, the Editor doing little beyond guardingthe interests of propriety, and toning down to mild reproofs the tortures inflicted on wickedstepmothers, and other naughty characters.These explanations have frequently been offered already; but, as far as ladies and children areconcerned, to no purpose. They still ask the Editor how he can invent so many stories-more thanShakespeare, Dumas, and Charles Dickens could have invented in a century. And the Editor stillavers, in Prefaces, that he did not invent one of the stories; that nobody knows, as a rule, whoinvented them, or where, or when. It is only plain that, perhaps a hundred thousand years ago, somesavage grandmother told a tale to a savage granddaughter; that the granddaughter told it in her turn;that various tellers made changes to suit their taste, adding or omitting features and incidents; that,as the world grew civilised, other alterations were made, and that, at last, Homer composed the'Odyssey,' and somebody else composed the Story of Jason and the Fleece of Gold, and theenchantress Medea, out of a set of wandering popular tales, which are still told among Samoyeds andSamoans, Hindoos and Japanese.

Click on any of the links above to see more books like this one.