- Welcome to FictionDB, Guest

- | My Account

- | Help

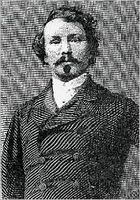

Ran Away To Sea — Mayne Reid

I was just sixteen when I ran away to sea. I did not do so because I had been treated unkindly at home. On the contrary, I left behind me a fond and indulgent father, a kind and gentle mother, sisters and brothers who loved me, and who lamented for me long after I was gone. But no one had more cause to regret this act of filial disobedience than I myself. I soon repented of what I had done, and often, in after life, did it give me pain, when I reflected upon the pain I had caused to my kindred and friends. From my earliest years I had a longing for the sea-perhaps not so much to be a sailor, as to travel over the great ocean, and behold its wonders. This longing seemed to be part of my nature, for my parents gave no encouragement to such a disposition. On the contrary, they did all in their power to beget within me a dislike for a sea life, as my father had designed for me a far different profession. But the counsels of my father, and the entreaties of my mother all proved unavailing. Indeed-and I feel shame in acknowledging it-they produced an effect directly opposite to that which was intended; and, instead of lessening my inclination to wander abroad, they only rendered me more eager to carry out that design It is often so with obstinate natures, and I fear that, when a boy, mine was too much of this character. Most to desire that which is most forbidden, is a common failing of mankind; and in doing this, I was perhaps not so unlike others. Certain it is, that the thing which my parents least desired me to feel an interest in-the great salt sea-was the very object upon which my mind constantly dwelt-the object of all my longings and aspirations.

Genres

Click on any of the links above to see more books like this one.